The Constitution of Canada is the country’s governing legal framework. It defines the powers of the executive branches of government and of the legislatures at both the federal and provincial levels. Canada’s Constitution is not one document; it is a complex mix of statutes, orders, British and Canadian court decisions, and generally accepted practices known as constitutional conventions. In the words of the Supreme Court of Canada, “Constitutional convention plus constitutional law equal the total constitution of the country.” The Constitution provides Canada with the legal structure for a stable, democratic government.

Sa Majesté la Reine Elizabeth II avec le premier ministre Pierre Elliott Trudeau signant la Constitution, 17 avril 1982.

The written Constitution is Canada’s supreme law. It overrides any laws that are inconsistent with it. The Constitution of Canada includes the British North America Act, 1867; the Statute of Westminster, 1931 (to the extent that it applies to Canada); the Constitution Act, 1982; any amendments to these acts; and the acts and orders that brought new provinces and territories into the Canadian federation.

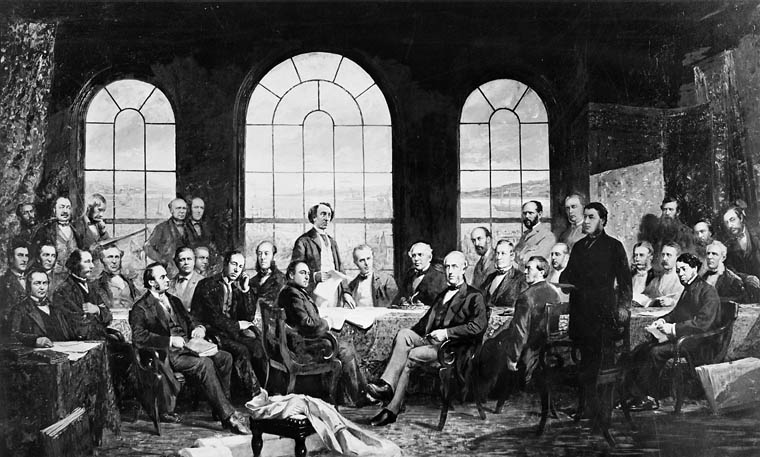

The British North America Act (now called the Constitution Act, 1867) merged three British colonies — the Province of Canada (present-day Ontario and Quebec), Nova Scotia and New Brunswick — into a new federation called Canada, with its capital in Ottawa. The British parliament passed the law at the request of the colonies. Their leaders met and agreed to its terms at conferences in Charlottetown and Quebec City in 1864. (See also: The Charlottetown Conference of 1864 and the Persuasive Power of Champagne; Quebec Resolutions.)

The BNA Act created four provinces: Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. It also provided for the admission of others. Power was divided between the federal Parliament and the provincial legislatures. The courts act as arbiters in cases of disputed jurisdiction. ( See also: Distribution of Powers; Federalism; Federal-Provincial Relations.)

La Conférence de Québec en 1864, tenue pour établir les bases d'une union des provinces de l'Amérique du Nord britannique.

The provincial legislatures were given power over: municipalities; hospitals; school systems; prisons; property; and provincial courts. There is joint federal-provincial responsibility over agriculture and immigration. Later amendments gave the federal Parliament the power to create an unemployment insurance system (1940) and clarified provincial jurisdiction over natural resources (1982). Court rulings have also assigned federal authority to several areas that had not existed in 1867, such as aviation, pipelines and telecommunications.

The authors of the BNA Act had intended for the federal government to be more powerful than the provincial governments. Yet over time, the provinces grew in power. In part, this was because of the growing importance of areas of provincial jurisdiction (such as social programs and natural resources). It was also due to a series of court rulings that favoured the provinces.

(© Aqnus Febriyant | Dreamstime)

The federal Parliament is composed of the monarch and two houses: the Senate and the House of Commons. There are now 105 members of the Senate: 24 each for Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritimes (10 for Nova Scotia, 10 for New Brunswick, 4 for Prince Edward Island); 24 for the West (six each for British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba); six for Newfoundland and Labrador; and one each for Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut.

Senators are chosen by the prime minister and officially appointed by the governor general. They hold office until age 75. (They were appointed for life until 1965.) Members of the House of Commons — Members of Parliament (MP) — are elected by popular vote. A general election is held at least once every five years. Each province and territory is allotted seats in the House of Commons based roughly on population. Each province is entitled to at least as many MPs as senators.

New bills must pass each house of Parliament and gain royal assent (from the governor general) before becoming law. Executive power is vested in the monarch. It is exercised at the federal level by the governor general, whose power is strictly limited by both constitutional convention and statute law. In practice, this means that the executive is headed by a prime minister and cabinet. They are accountable to Parliament for the affairs of government.

Each province has a legislature composed of a lieutenant-governor and a single legislative house. The house is elected at least once every five years. Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Manitoba had legislatures with two houses when they joined Confederation. They all later abolished the upper house. Executive authority is exercised in the same manner as at the federal level. The lieutenant-governor represents the monarch and the premier leads the government.

Les édifices du parlement de l'Ontario, à Toronto, illustrent bien le renouveau de l'art roman tardif des années 1890.

Also part of the written Constitution are the acts and orders that admit new provinces and territories. These include: the Manitoba Act, 1870; the Rupert’s Land and North-Western Territory Order (1870); the British Columbia Terms of Union (1871); the Prince Edward Island Terms of Union (1873); the Adjacent Territories Order (1880); the Canada (Ontario Boundary) Act, 1889; the Alberta Act (1905); the Saskatchewan Act (1905); the Newfoundland Act (1949); and the Constitution Act, 1999 (Nunavut).

The Statute of Westminster, 1931 was the all-but-final achievement of legislative independence from Britain. Under the statute, British law would no longer apply to Canada, except in areas where Canada asked Britain to continue to legislate. In 1931, Canada’s federal and provincial governments could not agree on how they would pass future amendments to the British North America Act. As a result, Canada asked Britain to keep the power to amend Canada’s Constitution until Canadians could come up with their own formula for doing so. Canada also used the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Britain as its highest court of appeals until 1949. This responsibility was then shifted to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Première page. (avec la permission de BibliothЏque et Archives Canada, Division des manuscrits)

The Constitution Act, 1982 gave Canada complete independence from Britain. Months of negotiations between the federal and provincial governments were held to determine how to “patriate” the country’s last British-held powers from Britain. The resulting Constitution Act, 1982 made several changes to Canada’s constitutional structure. The most important were the creation of an amending formula (the criteria that would have to be met to make future changes) and the addition of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Under the amending formula, most sections of the Constitution can be changed with approval from the Senate, the House of Commons, and the legislatures of at least two-thirds (seven) of the provinces, so long as those provinces contain at least 50 per cent of Canada’s population. (This is called the 7/50 rule.) Unanimous agreement of the Senate, the House of Commons and all ten provincial legislatures is required to abolish the Senate or to change the composition of the Supreme Court of Canada. It is also needed to change provisions that deal with: the offices of the monarch, the governor general, or the lieutenant-governors; the use of the French and English languages; and the right of a province to have at least as many MPs as senators.

Amendments that deal with some but not all the provinces (for example, changing the boundary between two provinces) may be made by the Senate, the House of Commons, and the relevant provinces. An amendment can proceed without Senate approval if the House of Commons approves the amendment and then does so again at least 180 days later.

Copie de la Charte canadienne des droits et libertés.

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees — and sets limits to — the fundamental rights and freedoms of Canadians. Under the notwithstanding clause, the federal Parliament or the provincial legislatures can exempt any law from certain Charter provisions for up to five years.

The Constitution Act, 1982 also reaffirms the existing rights of Indigenous peoples in Canada. However, it leaves these rights largely undefined. The Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees Indigenous peoples their rights under the Royal Proclamation of 1763; it specified that they would continue to hold all lands they had not ceded or sold. (See also Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Constitutional conventions are the unwritten rules of a system of government. They essentially fill the holes in the written Constitution. For instance, none of Canada’s constitutional documents defines the method of selecting the first ministers (the prime minister and the premiers) or the cabinets. This is governed by convention.

Conventions are in the political realm. They are not enforced by the courts. Courts have given opinions on the existence and application of conventions. It is up to voters to enforce conventions at the ballot box.

The Constitution Act, 1867 gives extensive powers in theory to the governor general and the provincial lieutenant-governors. Conventions strictly limit their personal discretion in the exercise of these powers in all but the most exceptional of cases. Governors general and lieutenant governors act only on the advice of ministers. They must follow that advice, so long as the government maintains the confidence of the legislature or Parliament, and the advice is constitutional.

When the office of first minister becomes vacant, the governor general or lieutenant-governor invites an individual who can gain the confidence of the legislature to become first minister and form a cabinet. In practice, this is almost always the leader of the party with the most seats. If no party can command the confidence of the legislature and form a government, an election is called. These conventions ensure that the government is accountable to the legislature and, by extension, to the electorate.

According to the confidence convention, when a majority of the members of a legislature no longer have confidence in the government, and express it through a vote in the legislature, the first minister must resign or ask the governor general to call an election.